“She’s a real spice cadet, that one.”

The speaker had an Aussie accent. Other than that, not much was registering in my sleep-deprived zombie brain that morning in Bombay’s landmark Victoria Terminus.

I turned to see which of the young male backpackers standing behind me had spoken, and found all three looking in the direction of the endless line of listless souls next to our endless line of listless souls. I knew immediately who had caught their attention. The “spice cadet” – “space cadet” in Canadian English – was an attractive, barefoot, sari-wearing blonde. She looked nonchalant, bored even, as she balanced a bundle on her head, not an uncommon sight in India, unless, that is, you happened to be a blonde spice cadet. Before refocusing on the task at hand – buying my ticket – I wondered what Spice Cadet’s story was.

My story on this spring morning in 1989 was that I’d gone trekking in Nepal with five Montrealers, and I was now nearing the end of a solo side trip to India that I’d tacked on.

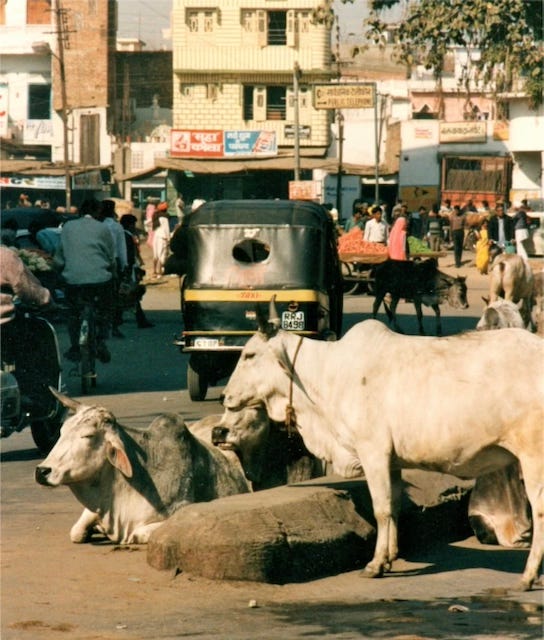

India had proven to be such an assault on my senses, though, that I decided, after a couple of weeks, to seek refuge from its crowds and clamour, heat and dust, bicycle-rickshaw hustlers, snake charmers and the sorry spectacle of bony cattle chewing garbage in the street. So, for a few days I chilled on a beach in the ex-Portuguese enclave of Goa. It was my passage from India, albeit a temporary one. Then, revitalized, I headed north by bus to Bombay – six years before it would officially change its name to Mumbai – where I planned to catch a train to New Delhi. I survived the overnight bus ride, with unrelenting Hindi pop music blaring from a ghetto blaster next to the driver, and at 7 a.m. I found myself in Bombay’s cavernous Gothic station, sweating rivulets while standing for two hours in a line leading to the ticket booths.

I can’t recall, and my diary doesn’t say, how I endured the next nine hours in that teeming, steaming station before I finally boarded the 4:15 p.m. train. I was travelling second class, which was essentially a free-for-all for crowded space, but my ticket at least entitled me to a designated second-class sleeper compartment. Finding it, I plunked down on a bench seat between two middle-aged men. One was tall, thin, dark-skinned and grey-haired; the other shorter with a light blue shirt covering a slight paunch. We exchanged nods. I assumed we were the compartment’s only occupants, but then I spotted a pair of smallish blackened feet dangling from a bunk above.

It was Spice Cadet.

Of all the second-class sleeper compartments in all of India, I thought as I channelled Humphrey Bogart in Casablanca, and this weirdo turns up in mine. (Unlike Bogey and Ingrid Bergman, though, this strange stranger and I shared no backstory.)

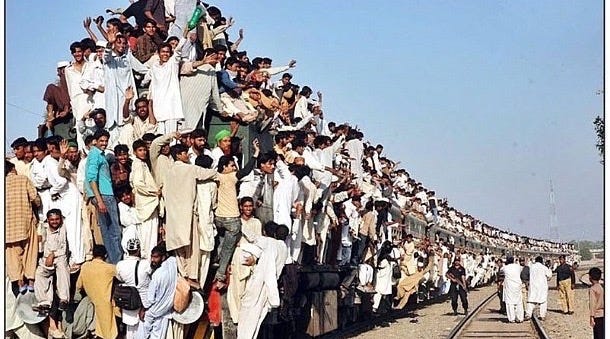

Our train pulled out of the station and slowly picked up speed. On our first stop, hordes of people stormed aboard, seizing whatever places they could find. The scene repeated itself at every stop along the 1,500-kilometre route. At each station, I would witness through the open window scores of men grabbing onto the sides of departing trains. I assumed there were also free riders, clinging to the exterior of our train, albeit out of sight from my vantage point. Those of us on the bench seats were getting squished by new arrivals. I asked the man in the light blue shirt, who’d by now moved up to the berth facing the one occupied by Spice Cadet, if he’d like to trade places. Normally, I’m too self-conscious to make a request that is almost certain to be turned down, but to my astonishment, he agreed. Maybe he felt claustrophobic under the low ceiling. He climbed down and I climbed up.

My diary, which so often languishes in superfluous detail when describing personal events, is maddeningly spare in chronicling the 29 hours I’d spend in Spice Cadet’s presence, during which we recounted our life stories as we rolled across the parched subcontinent. I do, however, recall her first words:

“Why do you wear shoes?”

“Uh, I dunno,” I said. “Just a habit, I guess.”

I asked her her name (Annemarie) and where she was from (Denmark), and volunteered my name and nationality. I wondered what our fellow travellers – all men – thought as they sat shoulder to shoulder below us like mannequins, saying nothing. Were they listening to our conversation? Clearly, they were far more experienced than I was at coping with such cramped conditions. At each new station they did their best to hold their ground against the invading mob. Those able to squeeze into our compartment would slam the door behind them. Then, when we pulled into the next station, new passengers would pour on and start banging on the door, hoping to join us. I felt sorry for the multitude left outside our compartment, sprawling on the corridor’s filthy floor. It got so crammed that, for fear of losing my place, I minimized trips to the car with the hole in the floor that passed for a washroom. (I could hold out longer then.) It was so hot in that rolling sauna that I had no appetite, and the low ceiling was too searing to touch.

Annemarie wasn’t the stereotypical statuesque Scandinavian. She was blonde, all right, but petite. Trained as an architect, she told me she had been unable to find work and went on welfare after leaving school. I didn’t believe her when she said she was 33: Annemarie had the face of someone more my age (40). She’d been in India for six months, so maybe the sun had aged her. I confess I liked that her sari didn’t hide her tight midriff. She told me about living in the jungle with an Indian family. Annemarie was a free spirit, into spirituality, with a side interest in illicit drugs. There was something masochistic about her; she wallowed in her privations and thought Indian-style squat toilets were superior to the sit-down western variety.

“In Denmark, all they care about is money and status and their comforts,” she said.

There was only a slight breeze coming through the window. Refreshment was limited to chai, sold for a few rupees by young men on bicycles on station platforms. They handed it to us through the bars of the window in small, crudely crafted, terra cotta cups. After stripping to my shorts because of the heat, I drifted off, and awoke shivering in the middle of the night. When the sun rose, we resumed our conversation above the heads of our silent, motionless fellow passengers. We finally pulled into New Delhi after 9 p.m., still on our bunks and roasting. For me, it was the culmination of an exhausting 2,100-kilometre, 53-hour bus-train odyssey.

In the train station, there was the usual mad scramble with aggressive cabbies. With her belongings again on her head, I watched Annemarie draw stares as she moved through the throng. Ironically, her efforts to go native made her stand out, not blend in. I didn’t know it then, because we’d made dinner plans for the following night, but this would be the last I’d see of her.

The next evening, when I turned up at the Metropolis Restaurant, near where she was staying, everything was as Annemarie had described it. The Metropolis was, indeed, a funky ’60s kind of place, full of young people. The sounds of Jim Morrison and the Doors’ “Come on, baby, light my fire …” filled the air. Food and service were top-notch, but Annemarie was a no-show.

•••

The world was less visually documented in ’89 than it is now, and so with no photos of Annemarie, let alone videos. I have only an aging man’s recollections to go on. These would include me lying in the suffocating, spartan YMCA room I shared with a couple of wall-climbing geckos, as I anticipated our dinner date – and who knew what afterward. Yes, Annemarie stood me up, so I can only assume our time together meant less to her than it did to me. No matter. We only had cameo roles in each other’s life story – minuscule ones, at that.

Annemarie rarely resurfaces in my thoughts these days but, when she does, I can’t help wondering where her life’s journey has taken her. Is she a retired architect living in Copenhagen, married and with grandchildren? Or is she as I remember her – frozen in time – still into spirituality, barefoot and sari-clad in India? Once a spice cadet, always a spice cadet?

Great story, Jim. You can meet interesting people on trains, and they can't get away from you. I know a woman who travelled with another girl east to west on the Orient Express in the 1980s. They got talking to a handsome young man who was on his own and spent the rest of the train trip with him. His name was David Bowie. This has been her dining-out story for decades.