There was no honeymoon. But, returning from their wedding, a new house near a bend in the Assiniboine River awaited Martin and Katie. A thatched roof covered walls made of hand-hewn logs, chinked with mud and sided with more mud mixed with manure, which was then whitewashed. A Ukrainian house.

It offered plenty of room for two people. But it must have been a shock for Katie, who had grown up in a house with servants. From relative comfort in a Galician village where her father was postmaster, she had come to the Saskatchewan backwoods to become the wife of a poor, unlettered farmer.

“Mercy upon me,” she thought. “Becoming my stepmother’s servant couldn’t be worse than this.”

Martin was 20. He already knew a life of relentless toil working for his father: Clearing the forest, removing the maze of stumps and roots, pulling up stones and moving them to sides of the fields, ploughing and planting, harvesting. Now he was on his own land, something he had longed for, but his homestead was a kingdom in name only.

His lot was Katie’s. She would help with field work, plant and tend a garden, bake bread in a clay oven next to the house, do all the cooking and preserving. And care of the children.

The first was a girl they named Marya, who entered the world on Dec. 4, 1910, and left it a few weeks later. For a visit with friends just before Christmas, Katie bundled the baby in several blankets and placed her in the straw that lined the sleigh in which they rode. Upon reaching their destination, she lifted the baby out of the straw.

“Martin, Marya’s not breathing!” Katie cried.

“May God forgive us,” Martin said.

The baby had suffocated.

More children followed. Six boys grew to manhood: Joseph (1911), Peter (1913), Michael (1915), Nicholas (1918), Stanislaus (1920) and Miroslaw (1926). Another girl died at birth in 1915.

Much of what follows comes from the memories of Peter, recounted late in life to his daughter Donna Nicholas, a fellow chronicler of our family’s story. Each child was born in the little house, with a midwife assisting. Peter remembered a gnarled old woman who sat in a corner smoking a pipe, waiting for the moment the baby’s head appeared before springing into action.

Because Peter, age 7, was old enough to recall the event, but not so old as to be chased out of the room, he might have been witnessing my father’s birth. The baby was christened Stanislaus, named after his mother’s father, the postmaster. But he was just Stan his whole life.

Copies of Martin’s tax filings for the years 1919-22 have survived. They reveal that by 1918, ten years after starting out, he had managed to clear only 45 of his 160 acres, on which he harvested enough grain – wheat and oats – for seed, animal feed and flour for the family’s bread. There was little left to sell.

Progress was slow on Martin’s land because of what he owed his father, Nick, who besides helping him build the house, probably supplied him with a horse or an ox, a cow or two, a few chickens, and the use of his machinery. Martin paid this off by working for Nick. Mutual assistance and the obligations that came with it extended to others close to the family. One of Nick’s daughters married a man named Andrew Gryba. He was a generous and kind man who helped Martin in his fields. So did Frank Barlishen, the man who introduced Katie to Martin.

Barlishen’s wife, Anne, and Katie had been friends in the old country, and so they remained in Canada. They were joined by Helen Hrywkiw, another neighbour. Helen was my mother’s aunt. This fateful connection brought my father and mother together many years later. (Helen gets married, Life Sentences, Jan. 3)

The three women were born in the old country, had gone to school there, and were literate in Ukrainian and Polish. They kept alive the language and culture they had known and brought with them to the wilderness.

Anne took part in amateur theatrical performances, staged in church halls. Young people performed as actors and musicians, made costumes and designed sets. The plays and musical performances were entertainment at a time when, except for weddings, there wasn’t any. Sometimes alcohol upstaged a performance, and an unintended spectacle ensued.

It might be said that Anne Barlishen died for her art. At a rehearsal in 1918, she contracted the flu, becoming a victim of the great pandemic, one of thousands who died in the Saskatchewan countryside that winter.

An indelible memory of Peter’s from that time: His mother and Helen walking barefoot on the path to church, faces darkened by the summer sun. Katie was slight, short and dark. Helen fairer, more robust. In the villages they came from, women often went shoeless. They wanted to feel the warm earth beneath their feet.

Women were more attuned to the solace that came from belief, especially the parts that called for forbearance, acceptance, humility and doing unto others. Katie instilled these fundamentals in her sons. Martin, though not a religious man, approved.

Katie read to her sons by the light of a coal oil lamp on winter evenings or on Sunday, and when the older ones were ready, she taught them to read and write in Ukrainian so they would not forget who they were, even as the Canadian school nearby turned them into who they would become.

She also taught her husband to read. A memory from that time: Martin and his brother-in-law, Andrew Gryba, taking turns reading stories aloud in front of the others, Martin’s lips moving haltingly to form the words. While he never learned to write, Katie showed him how to construct the letters in his name, so he could sign “Dimchinski” in place of the crooked X next to which, until then, she had to countersign with her own name. She created a new spelling for the family name. It wouldn’t be the last.

Life was hard, but as the 1920s rolled on the family was moving toward something better. There was even a chance to acquire more land, thanks to the machinations of Nick Demchynski. He came up with the idea of selling his well-developed home quarter to Martin, provided that he and his wife Tekla were able to continue living there. Martin would pay for the land partly in labour, partly with a bank loan, and, it was agreed, that in return for working the land, his son would be able to take some of its crop. It seemed a good deal all around. Nick would be relieved of some of his debt and Martin, now with more land, would ensure his sons’ futures.

Meanwhile, Martin and Katie’s 430-square-foot house was filled to overflowing. By 1926, when their youngest son, Miroslav, was born, there were nine people living there – husband, wife, six sons, and Uncle Julian. Julian Baran was one of Katie’s younger brothers. He arrived after she had, and had taken a homestead farther north in the bush. He had no wife. When swamp fever killed his livestock, he turned up at the Dimchinski farm. He never left.

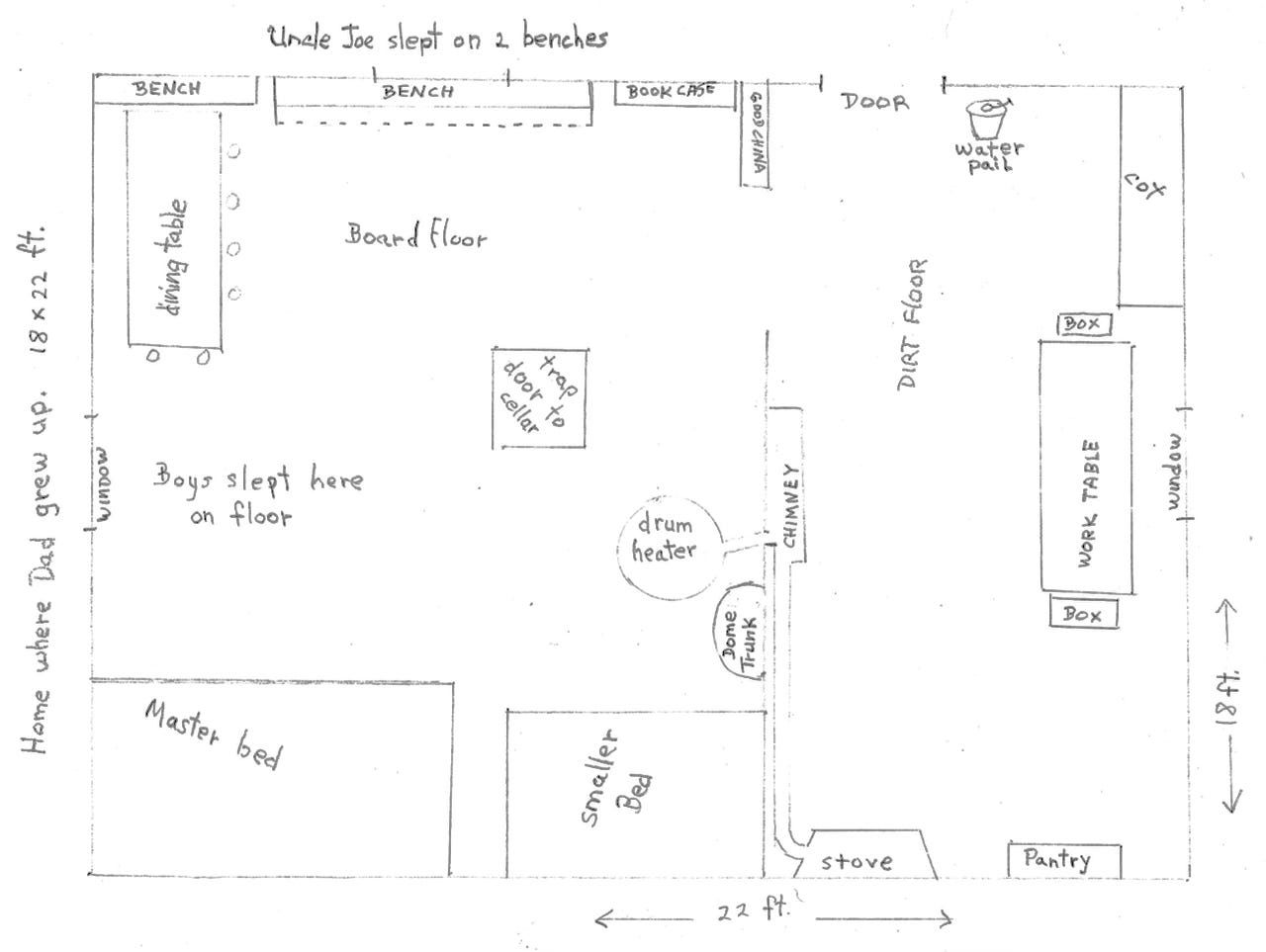

From the vantage point of 90-plus years, Peter, the second-eldest son, remembered in meticulous detail the house in which he grew up. He and his daughter Donna made a schematic drawing of it. There were two rooms, a dirt floor in the kitchen and board flooring in the larger room, used for dining, sleeping and socializing. A drum heater on the living-room side of the interior wall and a stove in the kitchen were connected to the chimney. Heating and cooking were entirely with wood. I’m guessing that Julian slept on the cot in the kitchen. Everyone else slept in the main room, the boys mostly on the floor.

Almost lost among the notations: In one corner of the larger room, a place for the family’s books and good china. The yearning for a better life that had brought them to the new land had a place in their home.

Hi Bryan. Please keep you family stories coming. They're always entrancing.

I may have mentioned before but our fathers had the same name, mine also went by Stan or Stash.