With the here and now having taken a gloomy turn, it’s time to reach back for a thread from the past. A couple of months ago, I wrote about one set of my great-grandparents, the Nikotas. Today I tell a story about Pytro Marcinkiw, my mother’s paternal grandfather.

Out of the mosquito-humming darkness the men appear leading a pair of horses pulling a wagon. On it is a wooden box, a hammered-together coffin.

Next to an overgrown thicket on the edge of a field, torchlight reveals a cottage built from rough-hewn logs, and beside it a church with whitewashed walls. Nearby are a few wooden crosses marking graves.

“Father! Wake up! We have something for you,” shouts one of the men.

A figure in night dress, confused by broken sleep, appears at the door of the cottage.

“Praise be to Jesus Christ!” he says nervously. “Praise be eternal!”

“Too late for that,” says Pytro. “You know who we are and why we are here.”

The priest’s features resolve into fear. He tries to run but he is quickly seized. There is nowhere to run, and even if he could run, insects and creeping creatures in this infernal wilderness would torture him mercilessly.

“Children – brothers – this is not God’s way,” cries the priest. “He says forgive our trespasses!”

“But it is our way,” Pytro says. “She is dead because of your sinfulness. You hypocrite! You shit! You are no man of God. The Devil hides behind your cross.”

The priest’s protests continue as the torch is put to the shack and the church. In the flickering glare, the men dig, taking turns, because the hole, while not wide, must go deep. When the box is pulled from the wagon, the priest’s fear turns to terror. The coffin is stood upright and the priest screams and struggles as he is stuffed inside. It is nailed shut. The coffin with its living corpse, is lowered into the earth, the priest still standing. Muffled howls are heard as the dirt falls onto the box.

“Now,” says Pytro, “You may look forever upon what you have done.”

“Did gido really bury the priest, Auntie?” the little boy asked the middle-aged woman. She was telling the story about the boy’s grandfather to a kitchen full of grown-ups. It was not meant for his ears.

“Sho’ boola, ’ta’ boola,” she told him, the rounded Ukrainian vowels lending a don’t-ask-me-more finality to her words: “What happened, it happened.”

The boy listening to the story about his grandfather was Reg Martsinkiw, my uncle. He is my mother’s youngest brother, and the last surviving member of their generation in my family. To complete the story as Reg heard it: Pytro had a little sister. She was an adolescent sent to cook and clean for a recently arrived priest. He seduced the girl and impregnated her. She died in childbirth with her baby. Pytro and his neighbours buried him alive. Pytro was so fond of his little sister that he told his people that he wanted to be buried next to her when he died so he could look after her in eternity. When Reg repeated the story to me, I, like him, savoured the pungent details.

But did it really happen?

To answer the question requires a journey into the minds of Ukrainian-speaking settlers, who near the turn of the 20th century uprooted themselves from insular villages in a distant corner of Europe to seek a more prosperous life in a still-young Canada. They cast themselves into an alien landscape where they faced challenges almost beyond their imagining. But imagine they did, and, because most of the newcomers were illiterate, they made sense of their experiences the only way they knew how, by way of stories – a kaleidoscope of honest remembering, tall tales, fabrications, embellishments, jokes, BS, and allegorical fables brought from the old country and given a new setting on the Prairies. During fallow seasons people recounted stories at kitchen tables, women gathered for communal chores like plucking chickens told them, as did men on beer breaks working together during harvest. They were in fact the same story, one of survival. There was a lesson or an element of truth in many, maybe most of them, even as what actually happened was twisted this way and that.

There was a church that burned near where Pytro Marcinikiw lived. It was called St. Demitros, named for a fourth-century holy man venerated by both Orthodox Christians and Catholics. Pagans martyred him, running spears through his body for his profession of faith in a Christian god. St. Demitros’s graveyard remains, today belonging to no religious order but cared for by descendants of people buried there. And there is a priest’s grave among them.

When Uncle Reg passed the tale of my great-grandfather on to me, it became my story, too, and I now have license to offer my own version. In fact, what you’ve read above is embellished with writerly details – the mosquitos, torchlight, the words spoken in the diction of the language I grew up with. But the essential elements are what I heard – a story of revenge satisfyingly exacted.

Mary Lozinski, the woman who told the story about Pytro Marcinkiw and the priest, never knew my great-grandfather. He was already dead when she was born in 1913. Reg had heard her spinning the enchantment decades later. A couple people from the district I’ve spoken to had also heard the story, and, as is typical in oral history, there were different versions. In one account, Pytro does not appear at all. It was really more about the priest.

Although she never met Pytro, Mary knew his family well. The Lozinskis and Marcinkiws were from the same village in the old country, a place called Hlybochok. The two families and others from the village came to Canada in 1898 on the same ship, the Italia, and they settled close to each other in east central Saskatchewan. It was then a wilderness, but in a few years the village of Mikado was founded near their homesteads.

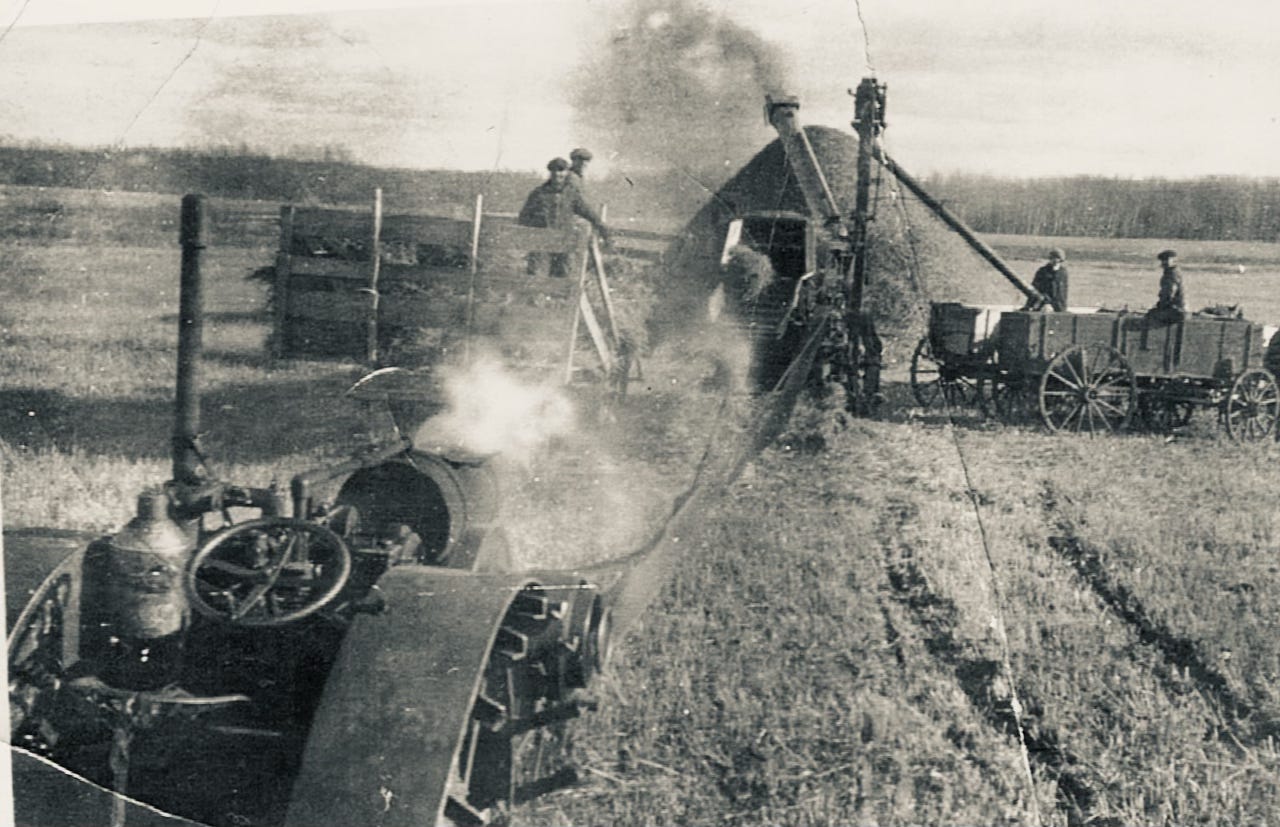

Mary was as much the subject of stories as she was a teller of them. As a girl, she was called a tomboy. She liked to ride her father’s workhorses and preferred to work in the fields with the men more than in the kitchen. In autumn, farmers got together to harvest each other’s fields. It was a more efficient way to work when they pooled their labour and machinery. Harvest crews were usually all men, but for many years Mary was part of one run by my grandfather, Pytro’s son. She was a “field pitcher,” whose job was to toss bundled sheaves of wheat into the threshing machine

Photos from 1928 show my grandfather’s threshing crew. In one, a figure on the wagon to the right appears to be a woman. That would be Mary when she was 15.

In 1934, Mary married Joe Lozinski. Her maiden name was Heshka, and she was from an Orthodox family, while Joe was a Ukrainian Catholic. But by then those distinctions didn’t matter as much as they once had.

Mary continued harvest work after she married. According to Reg, she once gave birth in a field. She took the newborn on a wagon back to her and her husband’s farmhouse, and she had dinner on the table for the threshing gang when it returned late in the evening.

Reg loved that story. I heard it a few times. Once, when Mary was a very old woman at some celebratory occasion where she was surrounded by friends and family, he retold it in front of her.

Was that really true? someone asked her. She chuckled. “Sho’ boola, ’ta’ boola.”

Next week: The search for Pytro Marcinkiw’s grave.

A perfect telling of a family story. You could use this for Memoir 101.

Gloomy is good, especially when it involves burying someone alive! As we discussed in your workshop, even if this particular event never happened, you know damn well that it happened to someone at some point in history, and probably will again, deserving or not.